“Who is to say that robbing a people of its language is less violent than war?” —Ray Gwinn Smith “Who is to say that robbing a people of its language is less violent than war?” —Ray Gwinn Smith

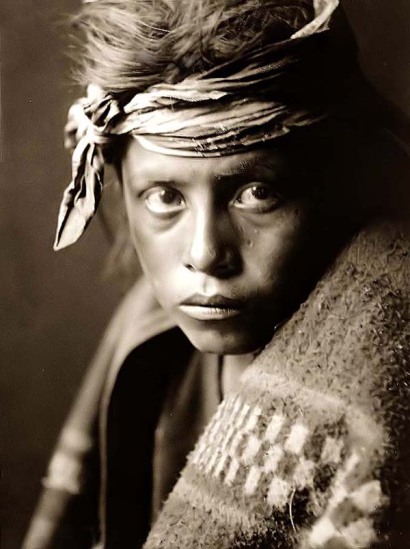

by Alfonso Valenzuela In this issue of The Cultural Knowledge Newsletter, I pay tribute to our Native American brothers from the Navajo Nation, which includes parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. They—like millions of brown-skinned “Americans” whose ancestors co-existed in the Southwest long before an invading European contingent stepped foot on this continent—also know about “linguistic prejudice.” Their experience in this country as true “Americans,” has something in common with us mestizos—the direct descendants of the Spanish Conquistadores and Mexican Indians. Other than sharing physiological similarities such as skin color and height, perhaps the most significant feature that sets us apart from individuals who migrated here from Europe, has to do with linguistics. Our native languages as well as our physical characteristics make us different from the majority population whose linguistic origins came from another continent. In spite of our linguistic differences, we have contributed in many ways to the growth and development of our country—at peace and at war. And, at different time periods in the history of our nation, people who choose to preserve their identity through their cultural values traditions, customs and language, fall out of grace with those who have lost theirs. But, we will talk about that some other time. During World War II, a former military serviceman fervently sought a way to help the US devise a code to transmit and receive messages by telephone and wire, that the Japanese military could not break. Philip Johnston, who came to northern Arizona on a covered wagon with his missionary parents, firmly believed that using Navajo men who had proficiency in their native tongue and English, could deceive the Japanese. His early formative years living among the Navajo provided him with the best cross-cultural education, by playing games and learning how to speak the language of his friends. He became so proficient in Navajo that in 1901 at age nine, he served as interpreter when he accompanied his father and two elderly Navajo leaders to Washington, D.C. to talk with President Theodore Roosevelt. His interest and concern for fair treatment of the Navajo and the Hopi prompted the young boy’s father to appeal directly to Roosevelt for help. At the time, the US considered the land where the Navajo lived, public domain. As a result of that meeting, Roosevelt agreed to withdraw that area from sale or settlement; several months later, he went further by issuing an executive order designating that land a reservation, known today as the Leupp Extension. The idea of using Navajo males to serve in the military as Communications Personnel has an interesting background. After Philip Johnston had finished his military service during World War I, he went to college and graduated with a degree in civil engineering. He went to work in Los Angeles as a civil engineer soon after completing his studies. During this time, he gave lectures about the Navajo culture and described his experiences as a young boy. Meanwhile, he kept reading about the US military’s inability to come up with a fail-safe secret code for transmitting and receiving messages by voice and wire during combat. He felt an obligation to his country even though he had already served his tour of duty in World War I. Feeling frustrated and eager to find a solution, he decided to get in touch with the US Marines to describe his proposal to use Navajo young males as communications personnel. He had no doubts that his plan would work and make a difference for our men in combat. His chance came on February 1942, when he met with Marine Lieutenant Colonel James E. Jones, Area Signal Officer of Amphibious Corps, Pacific Fleet, headed by Major General Clayton B. Vogel. This meeting took place at Camp Elliott, just north of San Diego. Philip Johnston felt confident that the use of Navajo as a code language by the Marine Corps in voice transmission—radio and wire—would work. Moreover, he assured them that no one could break security. He now needed to prove his theory worked by actually showing the Marine Corps commanders how it worked. With the approval of the top commanders at Camp Elliott, Philip Johnston took four Navajo males from Los Angeles, plus another one stationed in San Diego, to Camp Elliott on February 28, 1942 to put on a demonstration for the Marine Corps. In the test, two Navajos went into a room with six typical messages written in English used during military combat operations. These two men then transmitted the assigned messages in Navajo to the other two Navajos in a different room, who back-translated them into into English. Repeatedly, the Navajos showed that they could take voice or written messages in English, translate them into Navajo, transmit them in Navajo and then send those same messages back in English. Some very important military officers witnessed the simulated test, including Colonel Wethered Woodward, of the Division of Plans and Policies, the staff agency who would later make the final decision to recruit Navajo men to begin working on the project. With both Major General Vogel and Colonel Woodward acknowledging the positive results, Philip Johnston prepared the necessary papers to submit their recommendations to the Commandant of the US Marine Headquarters in Washington, D.C., in March of 1942. Initially, Major General Vogel had recommended the Marine Corps recruit two hundred Navajos who would become “Code Talkers.” But, the Marine Commandant limited the number of the first group to 30. Meanwhile, Philip Johnston put in for a waiver that would allow him to enlist in the Marine Corps in spite of his age and previous military service. He got clearance and ended up with the rank of Staff Sergeant, recruiting young Navajos for the Marine Corps and later training them in the code after finishing boot camp at Camp Pendleton. With the approval of the Navajo Tribal Council, the Marine Corps began locating and recruiting young Navajo men at Window Rock, Arizona, the capital of the Navajo Nation, in May of 1942. The Code Talkers had so much success throughout various campaigns in the Pacific that they became indispensable as communications specialists. According to Kenji Kawana in his beautiful tribute, Warriors: Navajo Code Talkers, “the way the code was set up, even an untrained Navajo who knew the language couldn’t make out what was said. Besides the alphabet words, they learned the 413 code names in a word test.” To give you a better idea of the training involved before assignments to combat areas, these Navajo Code Talkers had no easy task at hand. During their initial training at Camp Pendleton, recruits took 176 hours of instruction in communications procedures and equipment over a period of four weeks. They had a syllabus that covered a variety of subjects such as printing and message writing, the Navajo vocabulary, voice procedure, Navajo message transmission, wire laying, pole climbing and organization of Marine Infantry regiment, among other things. Because no words in Navajo existed for common military terms used in combat, the Code Talkers resorted to a very simple approach, which reflects their traditional way of seeking harmony with Mother Earth. Instead they came up with an oral code, taking familiar words from their native tongue, such as humming bird to designate a fighter plane, iron fish for a submarine, as well as using clan names for different Marine units. Also, these men had to come up with alternate terms in code for letters frequently repeated in the English language, consequently these letters had three variants that the Code Talkers used accordingly. To complicate matters even more, all Code Talkers had to memorize both the primary and alternate code terms while the basic material was printed for use in training in the United States. In addition, the Code Talkers could not take the vocabulary lists with them into combat areas to prevent the enemy from getting hold of them and compromising the entire project. They even faced danger from their own fellow countrymen, who mistook them for Japanese soldiers impersonating Marines in combat uniforms! Yet, they performed admirably everywhere they went and received praise from commanders at all levels. In The Navajo Code Talkers, Doris Paul cites G.R. Lockard, commanding officer of the Special and Services Battalion of the First Amphibious Corps at Camp Goettage, who sent the following message on May 7, 1943: “As general duty Marines, these people are scrupulously clean, neat, and orderly. They quickly learn to adapt themselves to the conditions of the services. They are quiet and uncomplaining and in eight months I have received only one complaint—a just one. In short, Navajos make good Marines, and I should be very proud to command a unit composed entirely of these people.” Kenji Kawano, who served in World War II in the First Marine Division’s Headquarters and Service Battalion, learned that one of the units in his battalion—the Division Signal Company—had Navajo Code Talkers. “By the end of the war, Code Talkers had been assigned to all six Marine Divisions in the Pacific and to the Marine Raider and Parachute units as well. They took part in every Marine assault, from Guadacanal in 1942 to Okinawa in 1945.” Until he came to Window Rock, Arizona in July 1971 to do research for the Marine Oral History Program, Kawano knew little about the Navajo culture. Because of his interest in the Navajo Code Talkers, he became official photographer of the Navajo Code Talkers Association. “Window Rock and the Navajo people were an entirely new experience for me, for not only had I no real knowledge of or an association with Native Americans, it was the first time I had ever been in an environment such as that in Arizona. It was an exciting and interesting experience, for I saw that the Navajo are beautiful and proud people who cherished and relished their traditions and customs despite the many years of effort on the American government to direct them into Anglo ways.” I offer the following testimonials from two Marine Code Talkers: “Throughout the war against the Japanese in the Pacific, we Code Talkers had to brush up on our codes at every opportunity. When the fighting got bad, words would fail us for a second; it was a good thing we [Navajo] have so many sounds in our language.”—William Kien, 4th Marine Division, Marshall Islands, Saipan, Tinian, Iwo Jima. “When I was inducted into the service, one of the commitments I made was that I was willing to die for my country—the U.S., the Navajo Nation and my family. My [native] language was my weapon.” David E. Patterson, 4th Marine Division, Roi Atoll, Marshall Islands, Kawajalein Atoll. I could add much more to this interesting, informative and amazing historical episode involving young men who lived in an isolated area, away from the many conveniences that others enjoyed—and took for granted—in populated areas all over the United States. They proved themselves in every way conceivable, proving their worth, intelligence, bravery, loyalty, sacrifice and patience, during a very critical period in our history. I have no doubt that had Philip Johnston not persisted in his belief that the Navajo language could serve as a communications system that no one could decipher, World War II would have had a different outcome. Finally, let me leave you with a thought, a phrase that I heard on Nova, broadcast by the Public Broadcasting Service, on KUAT-Channel Six, our local educational television channel : “Language is the mirror of humanity…and only by studying its reflections can we understand its contributions.” (October 5, 1995 Tucson, Arizona) Written by Alfonso Valenzuela, President, Cross Currents, International, Cross-Cultural Marketing Communications, 295 N. Meyer, #2, Tucson , Arizona 85701 June 1996c Tel.: (520) 882-2855 Fax: (520) 882-2855 . Sources for this article: Philip Johnston and the Navajo Code Talkers, Syble Lagerquist; Warriors: Navajo Code Talkers. Photographs by Kenji Kawano, Foreward by Carl Gorman, Code Talker and Introduction by Benis M. Frank, USMC; The Navajo Code Talkers, Doris A. Paul; Braided Lives: An Anthology of Multicultral American Writings, Minnesota Humanities Commission.

Questions and Comments: AZDBC@aol.com

© 1996-99 Cultural Knowledge, all rights reserved. Note from J. Mark Jordan: Our recent visit to Lawton, OK to attend the Native American Conference inspired this reprint. A Navajo church in New Mexico is affiliated with the UPCI and some of their members were at the conference. I have great respect for them and the work they are doing. You can reach them www.newcomblupc.com. |

Wednesday, September 5, 2007 at 07:40AM

Wednesday, September 5, 2007 at 07:40AM  Wednesday, September 5, 2007 at 07:40AM

Wednesday, September 5, 2007 at 07:40AM

Reader Comments