by Mortimer J. Adler, Ph.D.

by Mortimer J. Adler, Ph.D.

Dear Dr. Adler,

To tell you the truth, I find the so-called great books very difficult to read. I am willing to take your word for it that they are great. But how am I to appreciate the them if they are too hard for me to read? Can you give me some helpful hints on how to read a hard book?

THE MOST IMPORTANT RULE about reading is one that I have told my great books seminars again and again: In reading a difficult book for the first time, read the book through without stopping. Pay attention to what you can understand, and don’t be stopped by what you can’t immediately grasp on this way. Read the book through undeterred by the paragraphs, footnotes, arguments, and references that escape you. If you stop at any of these stumbling blocks, if you let yourself get stalled, you are lost. In most cases you won’t be able to puzzle the thing out by sticking to it. You have better chance of understanding it on a second reading, but that requires you to read the book through for the first time.

This is the most practical method I know to break the crust of a book, to get the feel and general sense of it, and to come to terms with its structure as quickly and as easily as possible. The longer you delay in getting some sense of the over-all plan of a book, the longer you are in understanding it. You simply must have some grasp of the whole before you can see the parts in their true perspective — or often in any perspective at all.

Shakespeare was spoiled for generations of high-school students who were forced to go through Julius Caesar, Hamlet, or Macbeth scene by scene, to look up all the words that were new to them, and to study all the scholarly footnotes. As a result, they never actually read the play. Instead they were dragged through it, bit by bit, over a period of many weeks. By the time they got to the end of the play, they had surely forgotten the beginning. They should have been encouraged to read the play in one sitting. Only then would they have understood enough of it to make it possible for them to understand more.

What you understand by reading a book through to the end — even if it is only fifty per cent or less will help you later in making the additional effort to go back to places you passed by on your first reading. Actually you will be proceeding like any traveler in unknown parts. Having been over the terrain once, you will be able to explore it again from points you could not have known about before. You will be less likely to mistake the side roads for the main highway. You won’t be deceived by the shadows at high noon because you will remember how they looked at sunset.And the mental map you have fashioned will show better how the valleys and mountains are all part of one landscape.

There is nothing magical about a first quick reading. It cannot work wonders and should certainly never be thought of as a substitute for the careful reading that a good book deserves. But a first quick reading makes the careful study much easier.

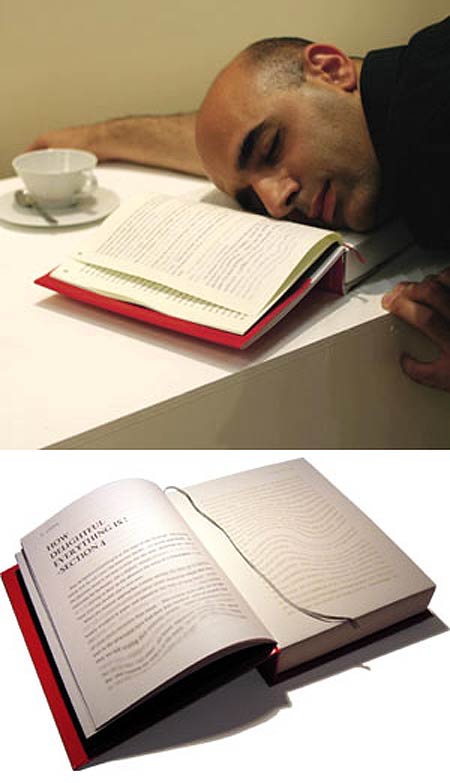

This practice helps you to keep alert in going at a book. How many times have you daydreamed your way through pages and pages only to wake up with no idea of the ground you have been over? That can’t help happening if you let yourself drift passively through a book. No one even understands much that way. You must have a way of getting a general thread to hold onto.

A good reader is active in his efforts to understand. Any book is a problem, a puzzle. The reader’s attitude is that of a detective looking for clues to its basic ideas and alert for anything that will make them clearer. The rule about a first quick reading helps to sustain this attitude. If you follow it, you will be surprised how much time you will save, how much more you will grasp, and how much easier it will be.